In order to encourage transparency and public participation in the rulemaking process, the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) generally requires that federal agencies, prior to finalizing a rule, publish and subject the rule’s content to public input through the issuance of a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM).1 However, the APA provides for certain exceptions if an agency can show that following these procedures is “impracticable, unnecessary, or contrary to the public interest.2” One such rulemaking approach is known as “interim final rulemaking”: a process whereby an agency issues a final rule without first publishing an NPRM, but provides the public with a post-promulgation opportunity to comment.3 While interim final rules (IFRs) generally become effective immediately upon publication in the Federal Register, interested parties are invited to comment by a specified date with the expectation that the agency will “consider those comments as part of the process of finalizing the rule."4

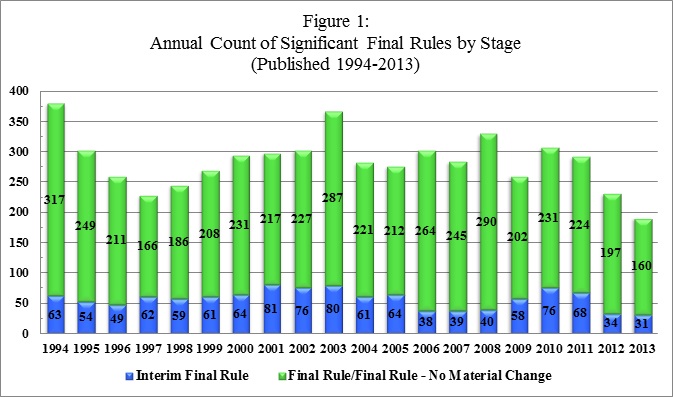

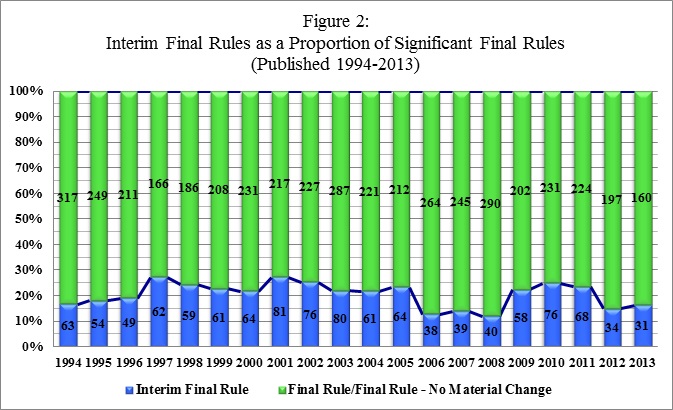

Although there are well known benefits associated with public participation during the pre-promulgation stage, interim final rulemaking represents an important mechanism through which agencies can respond to exigent circumstances, such as natural disasters or impending statutory or judicial deadlines, much more expediently than would otherwise be possible.5 To evaluate whether IFRs have become more common in recent years or otherwise exhibit clear trends of interest, we examined OIRA’s executive order review data on all significant final rules published by executive branch agencies between 1994 and 2013.6 While there is no clear directional trend over time, on average, IFRs represent 20.3% of all significant final rules published during the period in question.

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the variation over time; on the low end of the range, IFRs represented only 12.1% of all significant final rules published in 2008. This stands in stark contrast to 2001—the year with both the highest proportion and highest number of IFRs in absolute terms—in which IFRs represented more than a quarter (27.2%) of all final significant rules published. Upon closer examination, it becomes clear that much of the increase in IFRs that year was attributable to the federal government’s response to the September 11th attacks. While further research would be necessary to confirm a consistent correlation over time, this serves to support the general assumption that sudden increases in the number of IFRs are often associated with emergencies that require time-sensitive agency action (consistent with the exemptions to notice and comment provided by the APA).

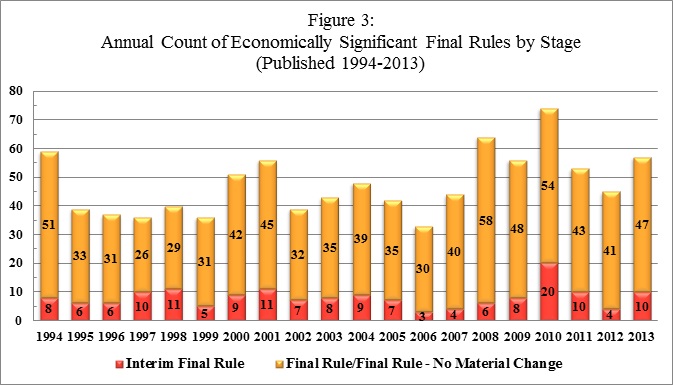

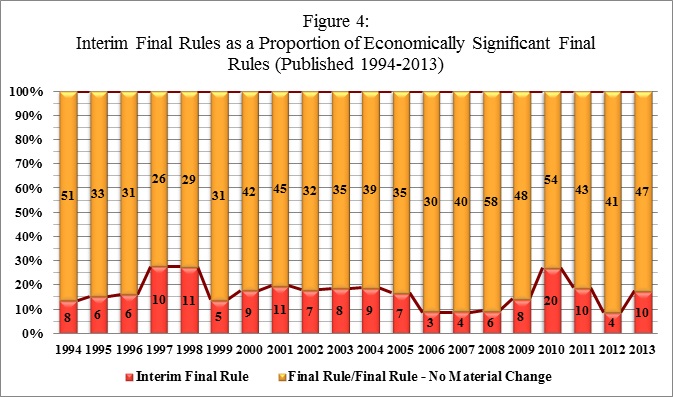

As Figures 3 and 4 illustrate, IFRs represent a smaller percentage (17%) of “economically significant rules,” which are those expected to have an impact of $100 million or more in a year. The large number of economically significant IFRs issued in 2010 is largely due to implementation measures required by the passage of the Affordable Care Act.

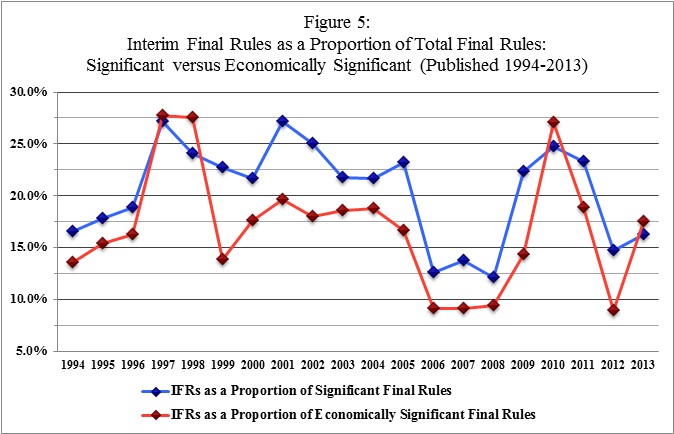

Figure 5 demonstrates that the number and proportion of IFRs fluctuates across years in a similar manner in both significant and economically significant rules.7

1 Vanessa Burrows and Todd Garvey, Congressional Research Service, R41546, A Brief Overview of Rulemaking and Judicial Review, (January 4, 2011).

2 Administrative Procedure Act, U.S. Code 5, § 553.

3 Maeve Carey, Congressional Research Service, RL32240, The Federal Rulemaking Process: An Overview (June 17, 2013).

4 Michael Asimow, “Interim-Final Rules: Making Haste Slowly, 51 Admin. L. Rev. 703 (1999).

5 Michael Asimow, “Interim-Final Rules: Making Haste Slowly, 51 Admin. L. Rev. 703 (1999).

6 Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, Search of Regulatory Review, (2014).

7 Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, Search of Regulatory Review, (2014).