Download this insight (PDF)

Introduction

When Donald Trump returns to the White House in January 2025, he has indicated that his administration will seek to reverse many Biden administration policies. These reversals will include regulations, one of the most common and important ways in which the Biden administration has advanced its policy priorities. If past is prologue, one prominent tool that President Trump—in tandem with Republican congressional majorities in the Senate and House of Representatives— will use to eliminate Biden-era regulations is the Congressional Review Act (CRA).

The CRA provides Congress with fast-track provisions to overturn recently-issued regulations. While these provisions can be deployed at any time, they are most potent in the “lookback period” following presidential transitions. The lookback period begins 60 working days before the end of a session of Congress. Regulations issued between that day and the beginning of the subsequent session of Congress are available for review in the new session of Congress.

Because the lookback window is calculated by counting backwards from the end of a session of Congress, it is impossible to know what the date will be in advance of adjournment. The GW Regulatory Studies Center’s CRA dashboard provides an interactive platform for exploring what rules might be available for congressional review under the CRA given different lookback windows. In this Insight, we highlight what we know so far about what regulations might fall in the lookback window, and how the composition of regulations might change based on different lookback windows.

In 2017, Congress passed and President Trump signed an unprecedented number of CRA resolutions disapproving of Obama administration regulations. Given the incoming administration’s own campaign promises to do so and the similar circumstance of Republicans in control of both the House and Senate, it is reasonable to believe that the Trump administration will seek to utilize this tool when it takes office in January. Our data show, however, that President Trump may have fewer significant opportunities this time, as the Biden administration finalized some of its most important regulatory priorities prior to the lookback window, therefore protecting them from elimination under the CRA.

How do different lookback window dates change the set of rules available for congressional review?

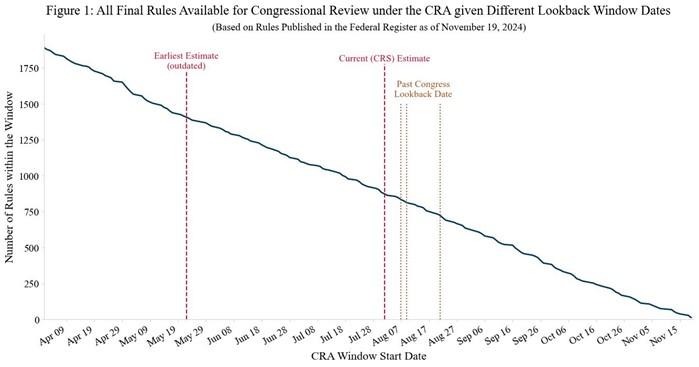

While the exact CRA lookback window is unknown at the moment, we examine the sets of rules that fall within the window under different estimates. Figure 1 shows how various start dates of the lookback window would change the number of final rules falling within the window, based on rules published in the Federal Register as of November 19, 2024.[1] An early estimate that gathered much attention is that the CRA lookback window would open around May 22. As shown in Figure 1, this date results in 1,406 rules falling under the window and therefore becoming available for elimination at the beginning of the subsequent session of Congress.

However as we addressed in a recent Insight, a May 2024 lookback date is impossible based on the Congressional schedule since the beginning of the year. Instead, the Congressional Research Service (CRS) recently predicted that the date would fall on or around August 1. The August 1 estimate would limit the number of rules subject to the CRA to 874, nearly 40% fewer rules compared to a lookback window opening on May 22.

In fact, Figure 1 indicates a consistent downward trend as the start date of the lookback window occurs later in the calendar year. The slope of this line is -8, meaning that for each additional day the lookback window is delayed, eight fewer rules fall within the CRA window. This figure also demonstrates that federal agencies have been issuing rules overall at a relatively steady pace since April.

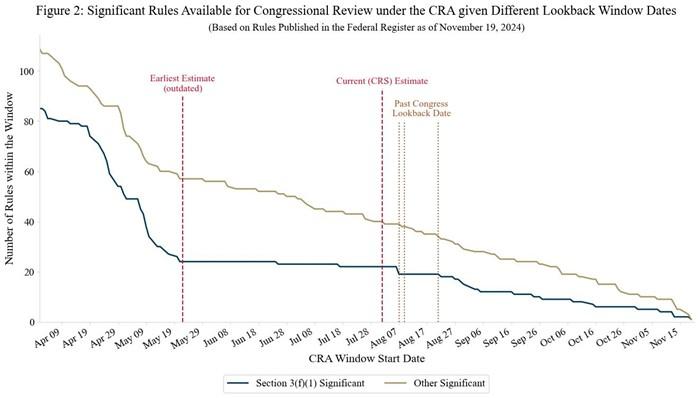

Agencies, however, have taken a different approach for significant rules. Figure 2 shows the number of section 3(f)(1) significant rules—those with an estimated annual impact of $200 million or more—and other significant rules[2] that would fall within the lookback window according to different start dates. A clear breakpoint occurs around the end of May, coinciding with the earliest estimated date of May 22. As we highlighted in a previous commentary, agencies rushed to finalize controversial, high-impact rules in April and early May this year, presumably to minimize the risk of CRA disapproval in case of a presidential transition. Consistent with that observation, a large number of significant rules will fall outside the CRA lookback window, even with the earliest estimated start date.

Figure 1. All Final Rules Available for Congressional Review Under the CRA Given Different Lookback Window Dates

Notes: Red dashed lines indicate the estimates of the CRA lookback date for the 118th (current) Congress, including the earliest estimated date of May 22 and the CRS estimate of August 1. Yellow dotted lines represent the actual lookback dates from the recent sessions of Congress, including the 115th Congress (August 7, 2018), the 116th Congress (August 21, 2020), and the 117th Congress (August 9, 2022).

While the May 22 start date puts 24 section 3(f)(1) significant rules (and 57 other significant rules) within the CRA window, the August 1 estimate covers 22 section 3(f)(1) significant rules (and 40 other significant rules), as of November 19. Since agencies issued few section 3(f)(1) significant rules between June and August, the later start date of the lookback window does not substantially change the set of such rules available for review under the CRA.

As the end of the Biden administration approaches, we will likely see the “midnight regulation” phenomenon, with agencies engaging in a flurry of regulatory activity before the administration ends. Although this will increase the number of rules falling within the CRA window, the surge of rulemaking in the spring suggests that this increase may not be as substantial as in previous administrations.

Figure 2: Significant Rules Available for Congressional Review Under the CRA Given Different Lookback Window Dates

Notes: Red dashed lines indicate the estimates of the CRA lookback date for the 118th (current) Congress, including the earliest estimated date of May 22 and the CRS estimate of August 1. Yellow dotted lines represent the actual lookback dates from the recent sessions of Congress, including the 115th Congress (August 7, 2018), the 116th Congress (August 21, 2020), and the 117th Congress (August 9, 2022).

Which agencies are issuing regulations that possibly fall within the CRA window?

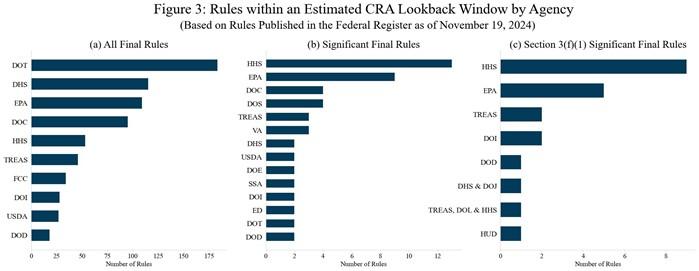

As the CRS estimate of August 1 is the most plausible lookback window start date at this point, we take a closer look at the rules that agencies have issued since August 1. Figure 3 lists the agencies that have issued the most rules in this period. Of the 874 final rules issued between August 1 and November 19, nearly 60% come from the Department of Transportation (DOT), the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and the Department of Commerce (DOC). This generally aligns with usual patterns in rulemaking activity, as these agencies regularly issue large numbers of rules addressing routine, non-significant issues, such as airworthiness directives (DOT), safety zone notices (DHS), state implementation plan approvals (EPA), and fishery limitations (DOC). Such actions are not likely to be targeted for CRA disapproval.

Figure 3: Rules Within an Estimated CRA Lookback Window by Agency

Notes: Panel (a) shows the top ten agencies that issued the largest numbers of final rules between August 1 and November 19. Panel (b) shows the agencies that issued more than one significant final rule during this timeframe, and Panel (c) lists the agencies that issued any section 3(f)(1) significant rules.

Looking specifically at significant rules, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and EPA issued larger numbers of rules than other agencies. Many of the HHS rules update payment system rates for the Medicare and Medicaid programs, which have historically not been popular targets for CRA disapproval. The EPA has issued nine significant rules—including five section 3(f)(1) significant rules—since August 1. Some of these rules concern relatively controversial issues and are plausible targets for the incoming Congress. We discuss these and other notable rules in the next section.

What rules might be targeted?

One major question is what rules will be subject to resolutions of disapproval at the beginning of the 119th Congress. Four section 3(f)(1) significant rules stand out as potential candidates for disapproval, while a number of non-significant rules may also be targeted.

Methane Emissions

EPA’s rule regarding Waste Emissions Charge for Petroleum and Natural Gas Systems on November 18, 2024 could be a candidate for a resolution of disapproval in the new Congress. The rule implements a portion of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) that directs EPA to collect a charge on methane emissions that exceed statutory thresholds. The Trump campaign has promised to repeal the IRA; using the CRA to overturn this regulation could jump start the new administration’s efforts to revert IRA policies.

Head Start

HHS’s August 21 rule Supporting the Head Start Workforce and Consistent Quality Programming might be subject to a CRA resolution of disapproval. This rule already has the attention of lawmakers: Government Executive reported that Senator Bill Cassidy (R-LA) has decried the rule—which would raise wages for teachers—for making Head Start more expensive, which could result in fewer children served.

Lead and Copper Rule

Another potential target is EPA’s National Primary Drinking Water Regulations for Lead and Copper, published in the Federal Register on October 30. The rule requires water systems to replace all lead service lines within 10 years of the rule’s compliance date. Nationally, this rule affects 9 million lead pipes, with a replacement cost of $20 billion to $30 billion. The expansive scope and price tag, as well as engagement from state attorneys general during the comment process, might make this rule salient for Congress.

Tobacco Age Limit

The Food and Drug Administration’s August 30 rule Prohibition of Sale of Tobacco Products to Persons Younger Than 21 Years of Age is yet another potential target. Although the rule does not exercise much discretion beyond the statute, lawmakers might view the rule’s increased age limit as an example of government overreach and eliminate it using the CRA.

Other Rules?

While highly salient rules such as these three gather a lot of attention, we would be remiss not to mention the possibility for other rules to be overturned. Our data show that 75% of the rules Congress overturned at the beginning of the first Trump administration were not major rules.[1]

The vast majority of rules issued in a year are not major rules. But while they may not meet that legal threshold, interest groups may be particularly in tune to rules that would have a meaningful effect on their regulatory environment. Those interest groups may sound a “fire alarm” to members of Congress, thereby drawing attention to rules they find particularly problematic. While we cannot offer insights about which regulations would be most attention-grabbing for industries and advocates, the CRA dashboard allows users to explore the universe of rules.

Looking Ahead

The data reflect the CRA’s increasing salience as a policy tool. The Biden administration’s issuance of significant rules slowed down dramatically around May 22, the lookback window estimate widely circulated earlier this year, showing their attention to the CRA. At the same time, members of the current Congress have introduced historic numbers of resolutions of disapproval targeting Biden administration rules. We expect to see the trend in introductions continue in the first months of the next Congress due to the lookback window. Beyond the CRA, the incoming administration will also use other tools to overturn regulations.

[1] The CRA applies to agency guidance, interpretive rules, and other types of rules that may not be published in the Federal Register. Because our data pulls only from the Federal Register, the figures presented here reflect the minimum number of rules available for challenge under the CRA.

[2] Significant rules are defined in Section 3(f) of Executive Order 12866, as amended by Executive Order 14094. In addition to 3(f)(1) significant rules, other significant rules include rules that would contradict other agency actions, alter budgetary impacts of certain programs, or raise legal or policy issues relevant to the president’s agenda.

[3] Major rules are defined by the CRA as having an annual effect on the economy of $100 million or more. 5 U.S.C. § 804 (2).