Download this insight (PDF)

The Congressional Review Act (CRA) “lookback date” has been a hot topic of conversation since the beginning of 2024. The lookback date denotes the start of the “lookback window”; any final rules issued during the lookback window are made available for review at the beginning of the subsequent session of Congress. If Congress passes and the president signs a joint resolution of disapproval, the targeted rule is repealed and no longer in effect. Much uncertainty surrounds the lookback date because it is calculated by counting back from the end of a session of Congress; until Congress finishes meeting for the year, there is no way to anticipate what the lookback date would be with any precision.

Moving into a tight race for the presidency, there is a real possibility of a transfer of power from one political party to the other in both the executive and legislative branches. If there is a political transition following the 2024 presidential election, a number of Biden administration regulations issued during the lookback window could be at risk of disapproval through the CRA’s fast-track procedures.

The lookback date estimate that garnered much attention—and raised eyebrows—predicted that the CRA lookback window would open around May 22. This prediction seemed to have influenced executive branch decision-making: In April 2024 alone, federal agencies promulgated an unprecedented 34 section 3(f)(1) significant rules, in an attempt to beat the anticipated start date of the lookback window. Even when these estimates were published earlier in 2024, a May lookback date was unlikely. The Congressional Research Service (CRS) now predicts that the lookback date would fall on or around August 1, 2024.

In this piece, I explain why it is so challenging to figure out the lookback date and present useful resources for counting days. I then present data and takeaways based on my own estimations of CRA lookback dates from 1996 to 2023, dispelling some misconceptions in the process. I also explain the trend towards later lookback dates we have seen in recent years and some of the procedural mechanisms that contribute.

Some Caveats

This piece will not cover the CRA’s basic mechanisms. For that, please refer to the Regulatory Studies Center’s overview of the CRA.

Only parliamentarians can provide official dates for the CRA’s time periods. This piece is not intended to provide any official guidance, but rather to offer insights into the day counting process. For official estimates, please defer to the parliamentarians.

What Does “Lookback Date” Mean?

While the CRA defines multiple time periods, this piece focuses on the period outlined in 5 U.S.C. § 801(d) that provides for congressional review of rules issued in the period starting either 60 session days in the Senate or 60 legislative days in the House before the date on which a given session of Congress adjourns, whichever date is earlier. I refer to this as the “lookback date” that represents the start of the “lookback window” or “lookback period” throughout this piece.

Rules that are issued during the lookback period are treated as if they are published in the Federal Register and reported to Congress on the 15th “working day” (either session day in the Senate, or legislative day in the House) of the next session of Congress. Legislators are then able to use the CRA’s fast-track procedures to review and potentially disapprove those rules.

The lookback period occurs every year, including years when there are no congressional elections, but it is particularly relevant following presidential elections. If there is a change in which party controls Congress, and if that party matches the party in the White House, the lookback period gives that new Congress a chance to overturn federal regulations from the prior administration without having to go through a new rulemaking process or pass substantial legislation.

What Does Counting Days Entail?

Brief Aside on Types of Days

To understand counting, it is useful to understand the difference between “legislative days,” which the CRA uses for counting days in the House, and “days of session,” which is the metric used for counting Senate days. Both chambers have legislative days, but different practices in the House and Senate regarding recess and adjournment make it more practical to count days in each chamber differently. Per the Congressional Research Service, a legislative day begins by convening the chamber following an adjournment, and it ends with another adjournment. A single legislative day can span multiple calendar days if a chamber recesses, rather than adjourns, at the end of the day.

A “day of session” is an informal term that describes a calendar day on which a chamber is in session. If a chamber stays in session past midnight and into the next calendar day, that subsequent day also counts as a day of session.

Counting Days

To count congressional days, one uses the Congressional Calendar, which is available online at govinfo.gov. Per the CRA, we count “legislative days” for the House.[1] The House typically adjourns at the end of each day, which means that legislative days in the House often correspond to calendar days. Occasionally a legislative day in the House will span multiple days; these are noted on the House calendars by enclosing the dates in brackets. Because the CRA employs legislative days for measuring time periods in the House, these bracketed days count as one day. Overall, each day marked and each bracketed set of days counts as one individual day towards the 60-day total.

To be more consistent with the House, the CRA uses “days of session” to measure days in the Senate.[2] The Senate frequently recesses overnight instead of adjourning, so it is more common to have a legislative day span multiple days in the Senate than in the House. As a result, a House legislative day is more analogous to a Senate day of session. Each day of session is marked on the calendar, including when a session runs over from one night to the early morning of the next day. Each day marked on the calendar counts as one day towards the 60-day total.

While one could count the days themselves, the simplest way to find the lookback date—at least for the dates in the House—is to refer to the Congressional Record. On or around the 15th legislative day of a session of Congress, the House Parliamentarian typically publishes a statement in the Congressional Record under the title “Rules and Reports Submitted Pursuant to the Congressional Review Act.”[3] In this statement, the House Parliamentarian publishes the start and end dates of the lookback period and the 15th legislative day of the current session, which denotes when members may start to introduce joint resolutions targeting last year’s rules.

Importance of Checking Both Chambers

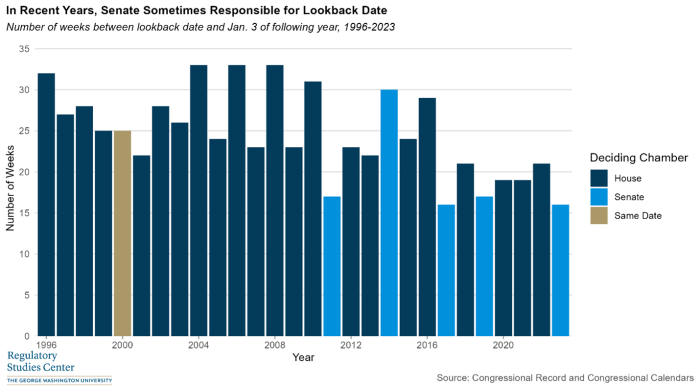

While a useful reference, the dates published by the House Parliamentarian only consider the House calendar and do not consider the Senate calendar. Because the statute explicitly says to use whichever date occurs earlier to determine the lookback period,[4] it is essential to check the Senate date. Although the conventional wisdom around the CRA is that the House always decides the lookback date, the Senate calendar has increasingly started controlling the date, likely as a result of the House meeting more often in the later months of the year than it has in the past. Figure 1 shows the length of the lookback periods in weeks, color coded by which chamber’s calendar decided the lookback date for that session of Congress.

Figure 1

For the first 14 years of the CRA (from 1996 to 2009), the House almost exclusively decided the lookback date.[5] But in the latter 14 years of the CRA (from 2010 to 2023), the Senate has decided the date 5 times—over a third of the time, marking a notable departure from the first half of the data. This runs counter to the conventional wisdom that the House always decides the lookback date. A better rule of thumb is that the House often, but not always, decides the lookback date.

Temporal Observations

Data

Based on outreach to a variety of academic and government sources, there is no singular dataset that compiles all of the lookback dates. To my knowledge, these are the first descriptive observations about the lookback dates. I gathered these data from the House parliamentarian’s publications in the Congressional Record, conversation with the Senate Parliamentarian regarding the most recent years, and my own estimates.

Each chart has 28 observations: the lookback date for each year from 1996-2023. Because the CRA uses the earlier of the date in the House or the Senate, I collected data from both chambers for each year to determine which chamber’s date occurred earlier and is to be used as the observation for that year. For all 28 House observations, the data come from the House Parliamentarian determinations published in the Congressional Record. Of the 28 Senate observations, the 9 most recent observations are from the Senate Parliamentarian’s office. I created the remaining 19 Senate observations (two-thirds of the Senate observations) through manual day counting; an unofficial count. The House date, published by the parliamentarians in the Congressional Record, determined the lookback date for all but two of those 19 years. As a result, all dates in the dataset excepting 2011 are from official parliamentary sources.

Findings

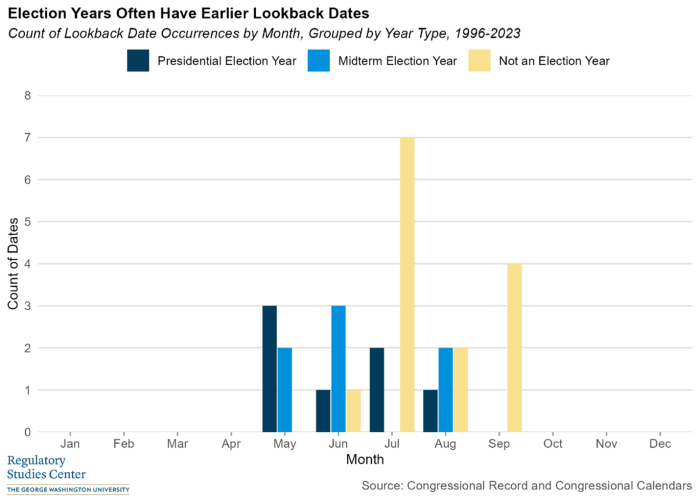

Figure 2 shows the number of lookback dates by month from 1996 to 2023. July is the most common month during which the lookback window starts, with 9 lookback dates occurring then. May, June, and August each have 5 lookback dates, while September has 4.

Figure 2

Figure 2 shows the overall distribution of lookback dates without differentiating between election years and non-election years. Figure 3 differentiates between presidential election years, midterm election years, and non-election years.

Figure 3

This chart shows that, while July is the most common month for lookback dates, most of the July observations occur during non-election years. Nine out of 14 lookback dates in election years were in June or earlier, whereas 13 out of 14 lookback dates in non-election years were in July or later. One explanation for the different pattern in election versus non-election years is that the House, in particular, tends to meet less frequently during the month of October in election years.[6] Meeting fewer days later in the year pushes the 60 day count earlier.

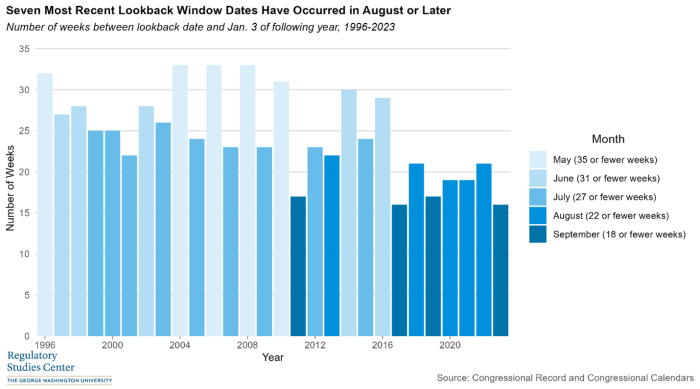

Regardless of the patterns shown in Figure 3, lookback dates are trending later. Figure 4 shows the elapsed weeks from the lookback date through January 3 of the following year, when Congress convenes its subsequent session, color coded by the month in which the lookback date occurred.

Figure 4

Since 2017, the lookback date has started in August or September. 2010 was the last year in which the lookback date occurred in May. This trend towards later lookback dates supports predictions that place the lookback date for 2024 in the late summer timeline.

One notable change in congressional behavior that contributes to this trend is the lack of “adjournment resolutions” in Congress. The Constitution includes an “Adjournments Clause,” which stipulates that neither house of Congress is allowed to adjourn for more than three days without the consent of the other.[7] Congress satisfies this requirement either by using a concurrent resolution in which the chambers of Congress give each other approval to adjourn, or by meeting in pro forma sessions—brief sessions in which Congress meets every three days for the purpose of not needing a concurrent resolution.

The last adjournment resolution was introduced in April 2017; the last successful adjournment resolution passed Congress in November 2015.[8] The lack of adjournment resolutions is particularly relevant for two time periods: the August recess and the end of the year. In both instances, the legislature has taken to holding pro forma sessions—which count towards the lookback period’s 60-day count—to avoid violating the Adjournments Clause of the Constitution. For the August recess, this means that each chamber briefly meets twice a week until they resume their regular schedule in the fall. Once Congress has finished its legislating at the end of the year, each chamber continues to meet briefly twice a week until January 3, when the next session of Congress is constitutionally required to convene. In the past, Congress would often adjourn in November or December.[9] One reason pro forma sessions have become more common is due to Congress’s use of the sessions to block presidents from making recess appointments. This practice has become more common since the 110th Congress in 2007-2008.

These days in session tend to add up to contribute to later lookback dates. For every year in which both chambers met under pro forma sessions during August, the lookback date has been in August or September. This is due to simple math: As Congress accumulates more working days at the end of the year, counting back 60 working days from the end of the year does not reach as far back into the calendar.

What Does This Mean Going Forward?

Of course, it is impossible to determine the lookback date before the 118th Congress adjourns. What we know, though, is that both the House and the Senate held pro forma sessions during the August recess, making it increasingly likely that the lookback date will fall in August.

A congressional session that results in a later lookback date has policy implications. When the lookback date falls later in the year, the lookback window is shorter. Fewer rules will be issued in that shorter window, meaning that a new Congress will have fewer rules to review.

The incredibly narrow presidential race in 2024 brings the policy implications to the forefront of the discussion. If the party in charge of Congress and the White House changes, Congress may use the CRA to overturn a number of Biden administration rules. However, the Biden administration’s push to publish a number of section 3(f)(1) significant rules in the spring has likely dampened the ability of Congress to use its fast-track procedures to overturn the rules with the largest impact.

[1] 5 U.S.C. § 801 (d)(1)(B)

[2] 5 U.S.C. § 801 (d)(1)(A)

[3] See as an example: Rules and Reports Submitted Pursuant to the Congressional Review Act, Congressional Record Vol. 170, No. 19 (February 1, 2024).

[4] 5 U.S.C. § 801 (d)(1)

[5] The only exception is in the year 2000, in which I estimate that the 60th session day in the Senate and legislative day in the House occurred on the same date.

[6] Author’s analysis of Congressional Calendars from govinfo.gov.

[7] Congressional Research Service, “Adjournment of Congress,” Constitution Annotated, https://constitution.congress.gov/browse/essay/artI-S5-C4-1/ALDE_00013353/.