In 1984 a French poultry researcher, Jean-Michel Faure, conducted a study to determine the optimal size of a chicken coop by letting the chickens manipulate the size of their cage. He squeezed egg-laying hens into a tight space but trained them to peck a button that would slowly expand the area of their coop. In theory the hens would stop pecking the button when they reached their preferred cage size. Turned out hens preferred a floor area of at least 63 square inches per bird.

Coincidentally, the latest tally of the amount of money it will take to run federal regulatory programs this fiscal year is $63 billion, a 0.7 percent increase over last year (adjusted for inflation). This is the latest data point in an unintentional experiment we have underway which looks like the reverse of Faure’s chicken cage trials, where we are slowly squeezing the budgets of regulatory agencies and hoping they can cope with it.

With the government’s debt held by the public now 75 percent of GDP, a post-World War II record, any increase in spending may seem generous but, for regulatory program managers, it is a reminder that they are living under increasingly tighter budget constraints than in the past. For example, from 2010 to 2015 spending on regulatory programs enjoyed average annual growth of about 2.6 percent above inflation. The decade before that the average annual increase was 5.5 percent in real terms, and the decade before that, the 1990s, it was over 4 percent. So this year’s increase of less than one percent above inflation is tight. And it is about to get much tighter.

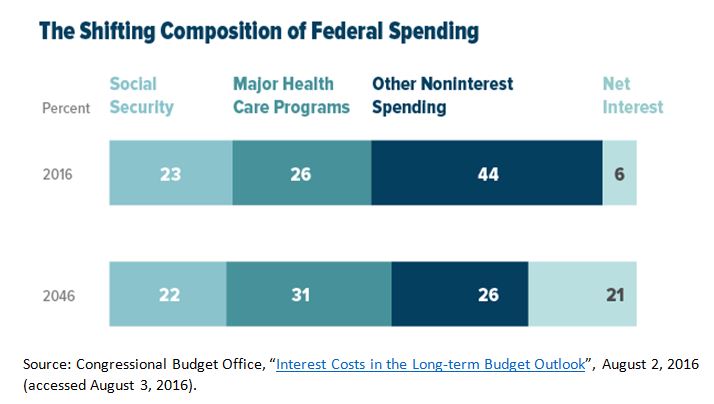

Last week the Congressional Budget Office highlighted a major shift that is taking place in government spending. This year, Social Security and health care programs account for almost 50 percent of the budget. Net interest payments on our debt accounts for another 6 percent leaving funding for all other programs, including regulatory activities, at about 44 percent (see figure below).

Over the next thirty years, on our current course, net interest payments on our debt are expected to increase to over a fifth of the budget leaving a much smaller slice of the pie for running the rest of government, including writing and enforcing regulations. This squeeze has already started, but it will intensify every year.

Of course, one way to prevent this big squeeze would simply be to make the pie larger by increasing taxes. By increasing revenues, and commensurately increasing spending, a smaller slice of a bigger pie could turn out to be roughly the same size. But it is tough to raise taxes, as tough as attempting to reduce spending on social security and health care. Regardless, it is extremely likely that the revenue from any increase in taxes would go to shore up social security and/or health care and/or reduce the growth in our debt before Congress or the president provided more funding to regulatory agencies. As columnist Richard Samuelson has pointed out, the slow strangulation of federal operations is, politically, “the path of least resistance.”

If they have not already done so, regulatory managers need to have a long-term strategy for dealing with the big squeeze. That probably means looking at a number of actions including:

- making process or personnel improvements (such as through a systems analysis like lean government) that either decreases costs, increases outputs or, hopefully, does both;

- cutting back or cutting out, low priority work (such as work products not required by law);

- reexamining the mission of the office or program and considering radical changes, including the use of new technology, that will allow the program to satisfy necessary requirements but at a greatly reduced cost (an approach called frugal innovation);

- increasing funding by expanding or creating fees and other types of receipts that can be spent by the program without prior Congressional approval; and,

- proposing changes to law (or other constraints) that will decrease the workload of the program.

This is, and will continue to be, a significant challenge for regulatory agencies, but it may be even more of a challenge for the next president.

Presidents come into office with their own priorities which often means additional work for regulatory agencies beyond what they are already required to do under existing statutes. For instance, Donald Trump has committed to modify environmental rules to help the coal industry as well as issue new banking regulations pursuant to the so-called Dodd-Frank Act. At the same time, Hillary Clinton has promised to issue more rules directed at, for instance, diminishing gun violence and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Both candidates have vowed to take actions that would require regulatory agencies to promulgate new regulations replacing or amending rules that were only recently placed on the books. For most regulatory agencies that will mean more work in a budget environment offering diminishing resources.

Researchers have found that chickens have a limit to how much space they prefer in their coop. We are now testing the limits of regulatory agencies to deliver more with less. If federal managers stay stuck in their current coops, the next president may end up with egg on her or his face.