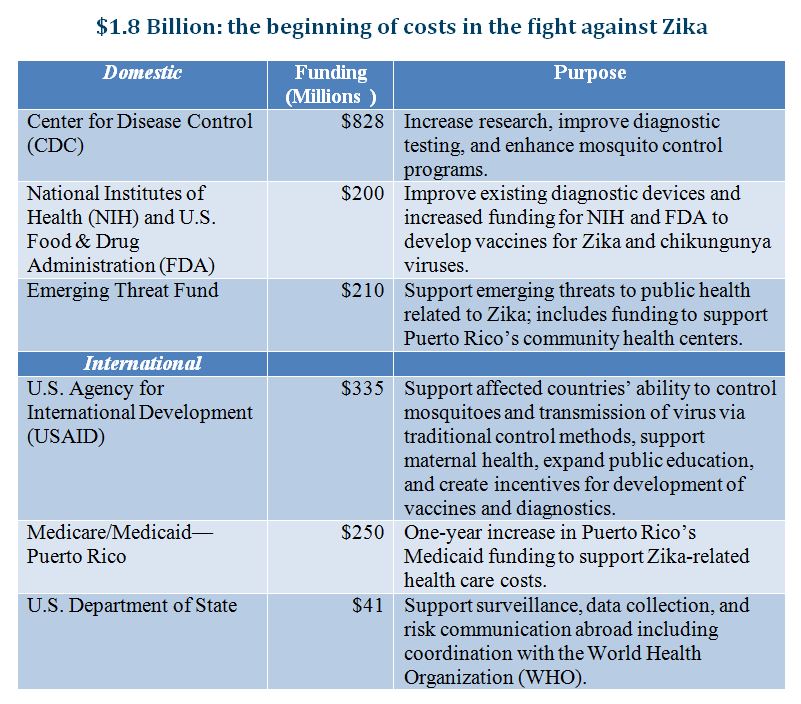

The Obama administration announced that it is asking Congress for $1.8 billion in funding to “prepare for and respond to the Zika virus, both domestically and internationally,” and the World Health Organization (WHO) recently declared Zika “a public health emergency of international concern.” Given the escalating concern over the spread of the Zika virus—transmitted mainly by mosquitoes—it is interesting to note that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has sat on a promising remedy for over 4 years. The agency has still not released for public comment its assessment of an application it received back in November of 2011 from the biotech company, Oxitec, for a field trial to employ a genetically modified (GM) mosquito with the potential to dramatically reduce the population of these disease-carrying insects.

Studies conducted on field trials in Brazil indicate that this method can reduce mosquito populations by up to 95% as opposed to more chemically-intensive methods, such as spraying insecticide. Additionally, this approach might be less expensive than using chemicals and could reduce the impacts that chemically-intensive control measures can have on people, other vulnerable species within the ecosystem, and the environment. The process of receiving FDA approval takes many years, and without pressure to begin public trials it is unlikely that we will have the option of using these GM mosquitoes to prevent the spread of mosquito-borne diseases, and respond quickly to urgent threats like Zika.

Regulation of Genetically Engineered Animals

Genetically modified animals hold great promise for improving public health and environmental outcomes, but their use in the U.S. is subject to oversight by the FDA, which regulates GM animals under the animal drug provisions of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act). FDA determined back in 2008 that, because GM animals contain modified DNA, they would be regulated as new animal drugs, defined as “an article…intended to affect the structure or any function of the body of…animals.” This interpretation of the FD&C Act makes it unlawful to introduce modified animals into commerce without FDA approval. One of the first steps in that approval process is review and public comment on an environmental impact assessment required by the National Environmental Protection Act.

It is at that early stage in the approval process that the Oxitec mosquito now languishes. FDA’s website states that it is reviewing the 2011 draft environmental assessment submitted by Oxitec “in consultation with government experts from other agencies” including the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). After over four years, it does “not currently have a timeline” for when it will move forward with presenting the draft environmental assessment for public comment. Since that is a prerequisite to field trials, the prospect of any action in time to address the growing Zika crisis looks bleak.

Regulatory Delays May be a Detriment to Public Health

A large body of academic research indicates that regulators like FDA that have authority to approve new products before they can be sold tend to systematically err on the side being overly cautious because delaying approval of beneficial products (a type II error) rarely harms their reputation because those benefits are invisible to the public, whereas approving a drug that turns out to be harmful (a type I error) brings negative attention. Essentially, the FDA overcompensates to avoid approving a product that might have negative effects (Congressional hearings, public excoriation, etc.) and, in exchange, creates unnecessary delays in its approval process for drugs that could save lives or otherwise improve public health outcomes during the period that they are not made available to consumers.

For example, the Florida Keys Mosquito Control District (FKMCD) plans to collaborate with Oxitec to conduct the field trial, once FDA approves it, within a section of its jurisdiction—Key Haven—in the Florida Keys. The FKMCD spends millions of dollars each year on mosquito abatement measures including regular spraying of insecticides and home visits to every single home in the Keys (every 3 months) to inspect for potential breeding areas and educate people on “best practices” for prevention. The use of Oxitec’s GM mosquito could produce significant savings for FKMCD, which admits that its current efforts only result in a maximum reduction of 50% in populations of mosquitoes. The FDA’s delay in approving trials results in a real opportunity cost borne by the citizens of the Keys, who could otherwise enjoy increased benefits in the form of reductions in the cost of mosquito abatement (which could be used for different public projects or tax cuts) and measurable increases in public health (fewer days being sick and fewer deaths and illnesses due to more effective abatement practices.)

Residents of the Keys are likely unaware of the financial and health costs they are incurring due to FDA’s long regulatory delay. Regulatory agencies often exhibit a strong status quo bias, particularly in areas as innovative as emerging biotechnology. Without the opportunity for Oxitec to publically showcase the results of a field trial in the U.S., the public will likely remain unware of the potential benefits in using a GM mosquito to reduce Zika outbreaks and the FDA will see no consequences for its inaction.

The Oxitec GM Mosquito

Oxitec, a British subsidiary of the American-owned Intrexon developed a GM mosquito of the species Aedes aegypti. Scientists modified the mosquito’s DNA to release a protein that hinders its cells’ ability to function in the absence of a certain chemical which is not found in sufficient quantities in natural environments. That is, they created an “autocidal” mosquito (left to its own devices, it dies.) The idea is to breed a significant number of male mosquitoes and release them into the population to mate. These mosquitoes would then pass on their autocidal DNA to their offspring, who would die before reaching maturity due the absence of the chemical they need to survive. The males and their offspring both die—leaving no GM insects in the ecosystem. There are several other benefits to utilizing this form of mosquito abatement:

- Only female mosquitoes bite, so the release of GM males does not expose the public to increased risk.

- Female mosquitoes usually mate only once within their lifetime, so this method effectively nullifies their ability to increase their population size.

- GM males only mate with other Aedes aegypti, which means this method targets a specific species of insect—compared to spraying insecticide—which could impact other vulnerable and/or useful insects.

- Reducing the need to use insecticide reduces the impact on the environment.

- This method reduces the spread of all mosquito-borne diseases transmitted by this species of mosquito, which includes: Zika, dengue fever, chikungunya, West Nile, and yellow fever.

Using a GM mosquito might also be more cost-effective than traditional mosquito-control efforts. For example, money spent on mosquito netting helps prevent people from being bitten while they sleep, but Aedes aegypti primarily bites people during the day. Additionally, money spent on spraying insecticide does little to eliminate any mosquitoes living indoors (it turns out that a significant number of them primarily rest and lay eggs indoors.)