Introduction

In 2017, the 115th Congress made historic use of the Congressional Review Act (CRA), previously described as an “arcane” or “obscure” tool, to eliminate 15 rules issued under the Obama administration. Depending on the outcome of the presidential election next fall, we may see the CRA used again.

Although the 117th Congress won’t convene until January 3, 2021, a looming deadline will affect what regulations they could eliminate using expedited procedures. According to the recently-released 2020 House calendar, any rules issued after May 19, 2020 may be subject to review by the 117th Congress. If Trump is reelected, this may not matter, since he could veto any disapprovals sent to his desk. Yet, statements by Trump administration officials suggest they are aware of the upcoming deadline and acting to finalize high-priority rules before the window opens. Rules issued within the window could face greater risk of being overturned—particularly under the scrutiny of a different group of political principals, depending on the outcome of the 2020 elections. However, agencies will have to weigh the benefit of rushing to publish their rules against the risk of shortchanging the quality of their supporting analyses.

What is the Congressional Review Act?

Congress enacted the CRA on March 29, 1996 to enhance congressional oversight of federal agency rulemaking. The law requires agencies to submit their rules to Congress before they can take effect. It also provides Congress with a mechanism for disapproving (i.e., eliminating) final rules issued by federal agencies. Only a simple majority vote is required in both houses to pass a disapproval. Additional “fast track” procedures, such as disallowing amendments and limiting floor debate to 10 hours, also prevent such resolutions from being filibustered in the Senate.

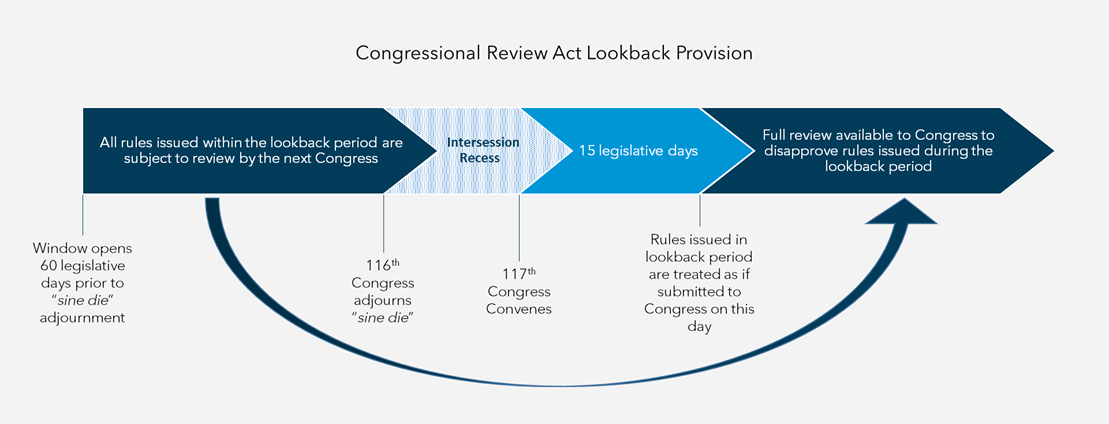

Perhaps most interestingly, the CRA contains a lookback provision allowing a subsequent session of Congress to disapprove any rules issued by agencies during the final 60 working days of the previous Congress.[1] This has historically been most relevant in the period immediately following presidential and congressional elections—where a new group of political principals can exercise this authority over rules issued under a different regime (i.e., a group with differing policy priorities). For example, for a rule issued in September 2020, the 116th Congress would have its usual 60-day window of review, but if the rule was issued during the last 60 legislative days that the House was in session, the lookback provision in the CRA would generate an additional full period in which the 117th Congress could review the rule.

What do we know about the 60-Day Lookback Window?

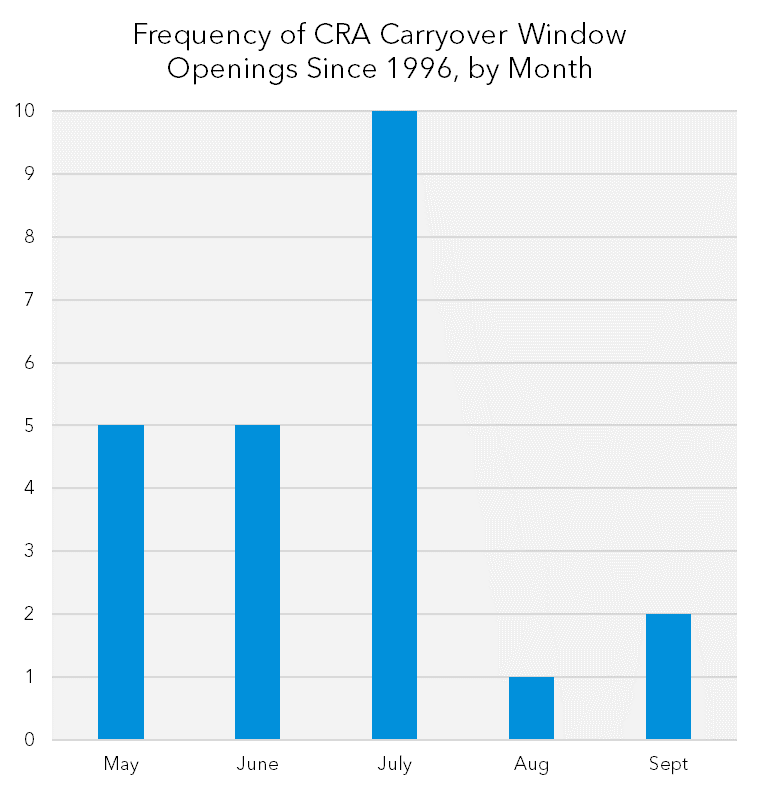

Due to the way working days in Congress are counted in the House and Senate, the House schedule has, to date, determined the window for the lookback period. According to the recently released 2020 House calendar, this window would open on May 20, 2020; all agency regulations issued on or after this date would be subject to CRA oversight by the 117th Congress.

This date is likely to change, however, because the House has historically convened more legislative days towards the end of each calendar year than what is presented in the tentative floor schedule. For instance, since 2011, using the House calendar released in December to predict the start of the lookback window results in estimates that are an average of 45 calendar days earlier than the actual start date. This suggests that the lookback period is more likely to begin sometime in July or even early August of 2020, but it will not be possible to definitively identify the start date until the 116th Congress adjourns for the last time. Regardless, the incoming Congress will have a new 60-day window to review those rules under the CRA beginning on its 15th working day.[2] In short, the 117th Congress and possibly a new President will have several months to exercise “fast track” oversight of approximately 6 months of regulations issued by the Trump administration. Altogether, this amounts to almost a full year of jeopardy for agency rules spanning two Congresses.

Implications for Agency Rulemaking in the Coming Months

Statements by Trump administration officials suggest they are aware that issuing regulations before the window opens on the CRA lookback period would protect these rules from expedited disapproval by the next Congress. In the absence of disapproval under the CRA, modifying regulations instead requires adherence to the more complex and time-consuming rulemaking process. A look at the recently released Unified Agenda indicates that agencies still have substantive regulatory priorities they plan to finalize within the next 12 months—including 119 economically significant actions. However, agencies will have to weigh the benefits of rushing to beat the CRA deadline against the potential risk of publishing rules supported by less-robust analysis. For instance, my colleagues at the GW Regulatory Studies Center found that better economic analysis could help regulations survive challenges in court. Traditionally, rules issued towards the end of presidential administrations are often supported by lower quality analysis. Regulators will have to carefully consider this tradeoff in any decision to rush to beat the clock—particularly given agencies’ numerous unsuccessful outcomes in court for regulatory actions issued under the Trump administration.

[1] 5 U.S.C. § 801(d). Due to differences in how the House and Senate count their chambers’ working days—legislative days and session days, respectively—the CRA stipulates that the window for rules included in the lookback period is calculated using whichever count grants the longest time for review.

[2] This date is calculated using either “legislative days” in the House or “session days” in the Senate.