Download this Commentary (PDF)

In brief...

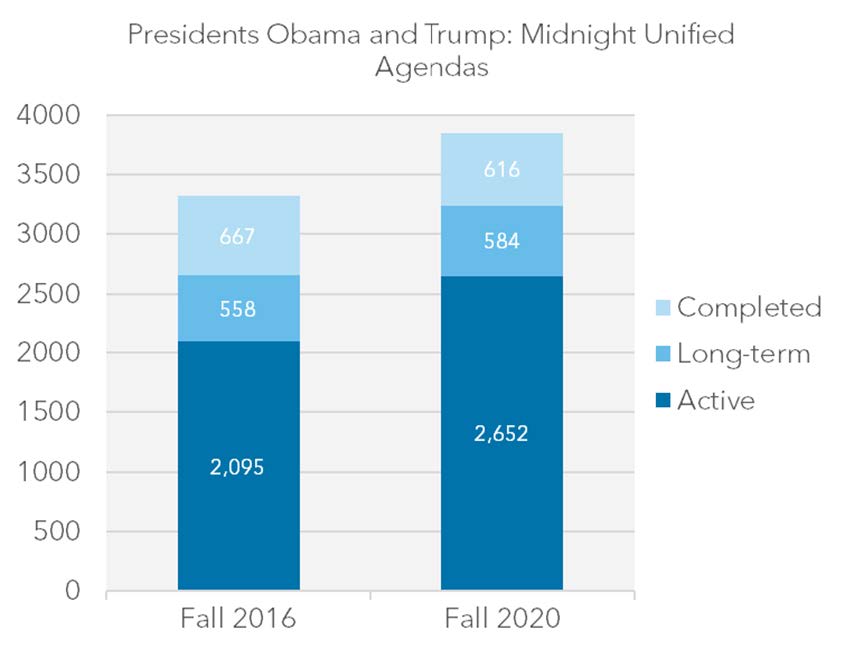

On Wednesday, the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) released its annual Regulatory Plan and semiannual Unified Agenda of Regulatory and Deregulatory Actions. It also marks the last Agenda to be published under the Trump administration. The contents of the Fall 2020 Agenda are likely to be of interest to much of the public—including members of the incoming Biden administration looking to perform a regulatory reset and begin implementing their own policy priorities.

Introduction

On Wednesday, the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) released its annual Regulatory Plan and semiannual Unified Agenda of Regulatory and Deregulatory Actions. It also marks the last Agenda to be published under the Trump administration. While the Regulatory Plan contains statements of agency priorities for the upcoming year, these may soon change given that the Biden administration is unlikely to continue the deregulatory efforts of Executive Order 13771. Notably absent are the Regulatory Reform Results for Fiscal Year 2020 detailing individual agencies’ performance under EO 13771, although the Introduction to the Regulatory Plan offers some topline estimates.

The Unified Agenda contains all actions currently in development at federal regulatory agencies, and this Agenda includes numerous “midnight” rules that agencies are racing to finalize before the next administration is sworn in on January 20. Since President Trump took office, the Agenda also classifies actions as either “regulatory,” “deregulatory,” but numerous rules fall outside of the order’s accounting requirements. The contents of the Fall 2020 Agenda are likely to be of interest to much of the public—including members of the incoming Biden administration looking to perform a regulatory reset and begin implementing their own policy priorities.

What's In the Fall 2020 Agenda?

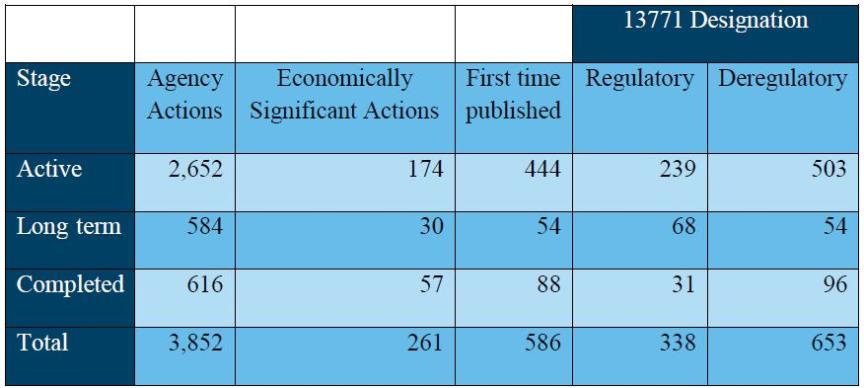

The Fall 2020 Unified Agenda contains a total of 3,852 agency actions, 338 of which are classified as regulatory and 653 as deregulatory. A whopping 2,861 actions do not count as part of the EO 13771 regulatory vs deregulatory accounting. Instead, these are classified as “other,” issued by independent regulatory agencies, or are otherwise not subject to the executive order. Of the total number of actions, 261 are economically significant.[1]

Actions in the Agenda are divided into their respective stages of development including: active (those where the next action is expected to occur within the next 12 months), long-term (those beyond the 12 month window), and completed actions (which includes rules that were either finalized or withdrawn since the last Agenda was published). Approximately 17% of the 2,652 active actions listed were published for the first time in the Fall 2020 Unified Agenda.

Table 1: Contents of the Fall 2020 Agenda

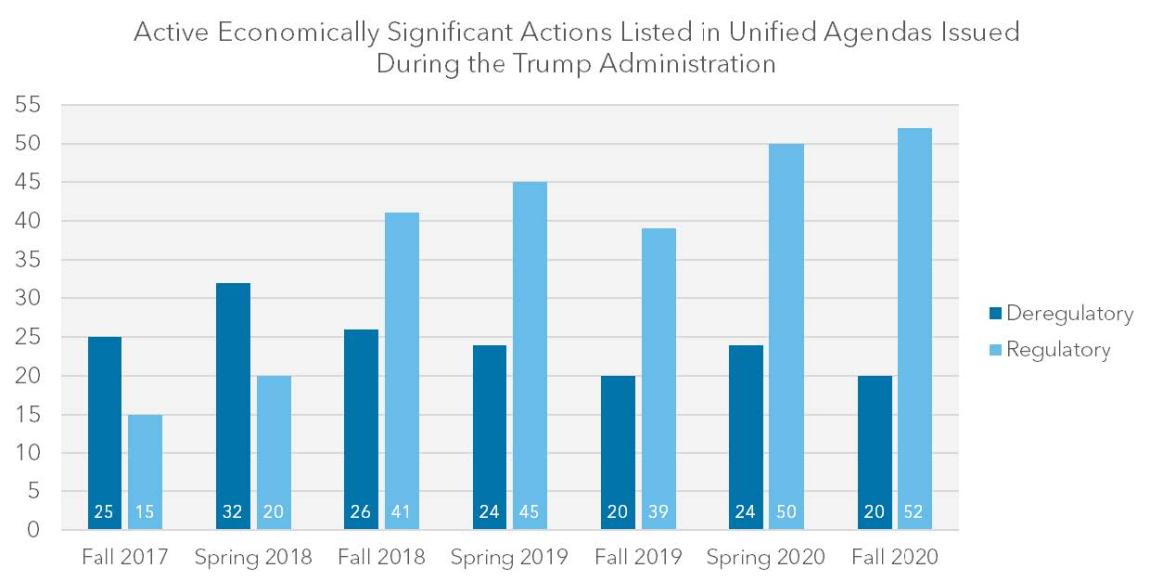

Additionally, in keeping with a more regulatory vs. deregulatory trend that I noted began in the Fall 2018 Agenda, with regard to economically significant actions, the Fall 2020 Agenda contains about 2.5 regulatory actions for every 1 deregulatory action.

Active Economically Significant Actions Provide a Glimpse of Midnight Priorities

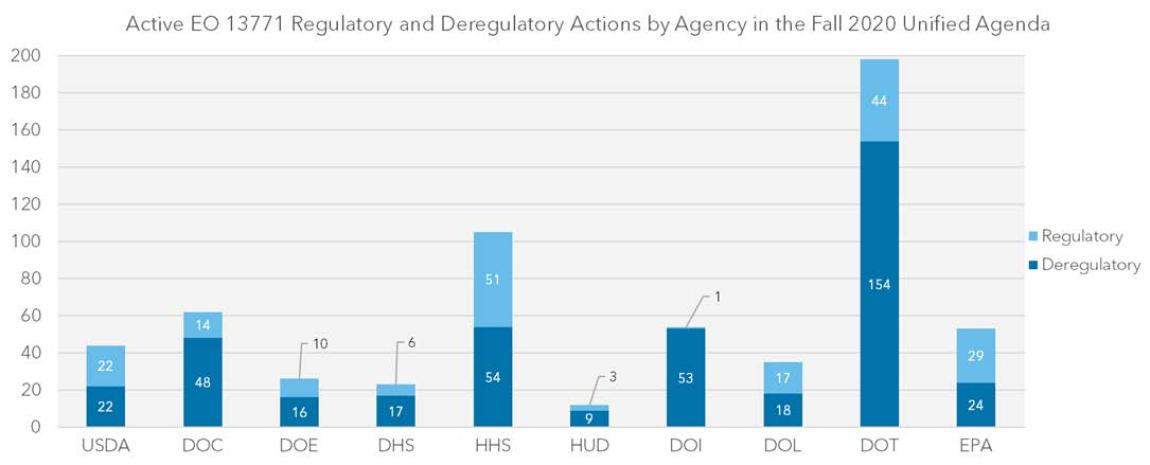

For agency actions listed as active, agencies plan to issue approximately 2 deregulatory actions for every 1 significant regulatory action.[2] However, this 2-for-1 topline estimate continues to be driven by outliers like the Department of Interior (DOI)—listing 53 deregulatory action with one single regulatory action. Additionally, the majority of actions in the Unified Agenda are not classified in the Unified Agenda as either “regulatory” or “deregulatory” under EO 1377. As my colleagues and I have recommended elsewhere, changes to this process could provide a more accurate accounting of agency regulatory output and allow for the public to independently verify OIRA’s reporting.

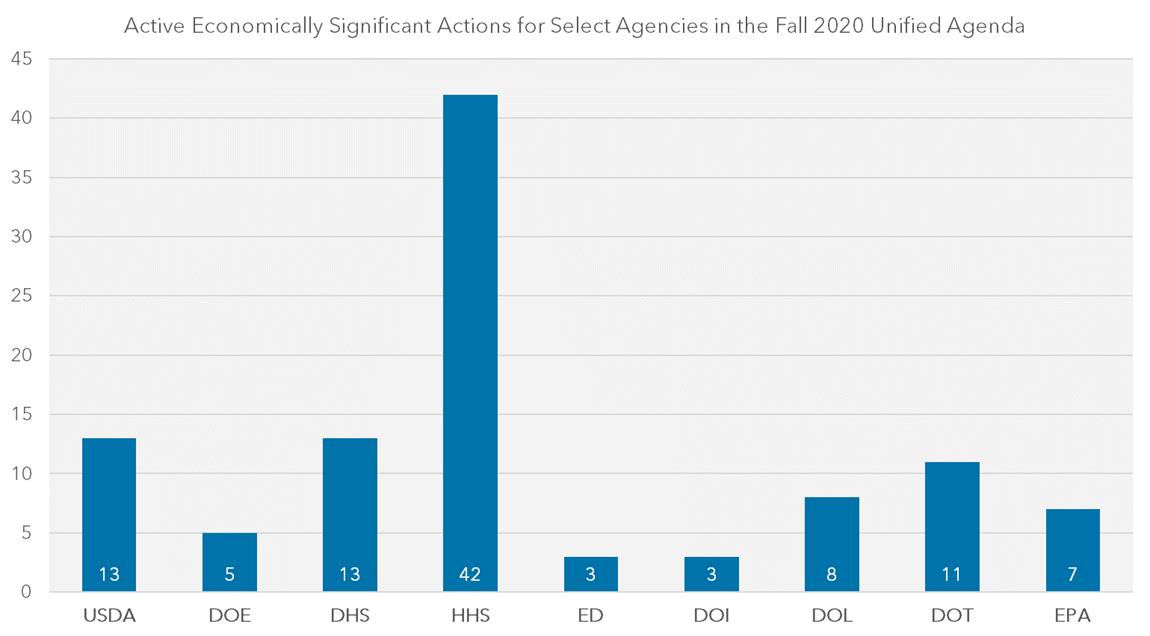

Economically significant actions provide a particularly useful measure of an administration’s regulatory output, and a look at the agencies with the largest number of planned active actions provides insight into the Trump administration’s midnight policy priorities. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is an outlier—with 42 economically significant regulations. This number is primarily the result of routine regulations issued by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Apart from HHS, the U.S. Departments of Agriculture (USDA), Homeland Security (DHS), Labor (DOL), Transportation (DOT) stand out in terms of their planned number of economically significant rulemakings.

Half of the actions listed by USDA involved changes to its Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). The DOT and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) economically-significant rulemakings include a mix of regulatory (12) and deregulatory (5) actions—mostly related to the environment. Almost half of DOL’s biggest actions and just about all of DHS’s most costly actions are related to increasing the stringency of immigration-related regulations which continues to be a policy priority for the Trump administration.

Several of these immigration-related rulemakings exemplify the potentially problematic characteristics of midnight regulations that often apply to last-minute rules. For example, some of my colleagues and I submitted public comments to DHS on its Collection and Use of Biometrics and Affidavit of Support on Behalf of Immigrants rulemakings—both of which fall short of existing executive branch rulemaking guidelines. For instance, they had unusually short comment periods (30 days instead of 60), and in both cases the agency shortchanged the quality of regulatory analysis supporting the proposal. Ultimately, the rush to finalize rules before January 20th could result in several rules with procedural deficiencies—making them potentially more vulnerable to legal challenges (i.e., increasing the likelihood that they will be overturned in court).

[1] According to Executive Order 12866, an “economically significant” regulatory action is one which has “an annual effect on the economy of $100 million or more or adversely affect in a material way the economy, a sector of the economy, productivity, competition, jobs, the environment, public health or safety, or State, local, or tribal governments or communities.”

[2] Based on OIRA’s guidance, more actions are likely to count as EO13771 “deregulatory” actions than “regulatory” actions. For instance, an action only counts as a “regulatory” one if it a significant regulatory action as defined in Section 3(f) of EO 12866 and that imposes total costs greater than zero. For a more in-depth explanation, see our report on EO 13771accounting.